Building a Euro Deterrent: Easier Said Than Done

Setting a baseline for Europe's new nuclear conversation

Six weeks since President Trump’s inauguration, the consequences of big, unfettered shifts in U.S. foreign policy are emerging. European leaders are considering a strategic deterrent independent of the U.S. nuclear arsenal for the first time. Previous discussions of a so-called “Euro Deterrent” assumed that U.S. nuclear forces would continue to serve as the ultimate backstop to deter Russia from strategic attacks against European allies and the United States itself. Increasingly, that may be a dubious assumption.

However, beyond rhetorical declarations, erecting and extending a credible Euro Deterrent through the combined forces of the France and United Kingdom will be incredibly difficult. The nuclear marriage between U.S. and Europe is not easily unraveled. NATO’s nuclear deterrent was developed to be credible, even beyond “until death do us part,” with coordinated plans, operations, and policies to convince allies that the United States would and could effectively defend them all from Russian strategic attack.

Ultimately, there is no replacing the U.S. nuclear backstop. The changes the United Kingdom and France would need to make as the European nuclear guarantors are considerable. As impossible as it may be to develop an America-less deterrent capable of defending Europe from Russia, the topic deserves further exposition if Europe intends to go down this road.

The Way it Is, and Why

As two officials with responsibility for nuclear policy in the Biden Administration, we along with many others see nuclear proliferation as a by-product of eroding U.S. security commitments. Over the course of our time in government, we worked hard to bolster these decades-old commitments. Since 1949, the United States formally extended its nuclear arsenal to the defense of European allies. Even today, NATO documents state:

Nuclear deterrence has been at the core of NATO’s mutual security guarantee and collective defence since the creation of the Alliance in 1949.

NATO’s 2022 Strategic Concept is explicit about the irreplaceable role of the United States in its security, which is and remains a “nuclear alliance.”:

The strategic nuclear forces of the Alliance, particularly those of the United States, are the supreme guarantee of the security of the Alliance. The independent strategic nuclear forces of the United Kingdom and France have a deterrent role of their own and contribute significantly to the overall security of the Alliance. These Allies’ separate centres of decision-making contribute to deterrence by complicating the calculations of potential adversaries. NATO’s nuclear deterrence posture also relies on the United States’ nuclear weapons forward deployed in Europe and the contributions of Allies concerned. National contributions of dual-capable aircraft to NATO’s nuclear deterrence mission remain central to this effort.

For more than seven decades, the United States committed to use its nuclear arsenal to deter strategic attacks against allies by Russia. As the U.K. and France developed their own nuclear arsenals and strategies, they did so with the luxury of a large U.S. nuclear backstop. The size and diversity of U.S. forces—nuclear and conventional— could credibly limit attacks by the massive Soviet military against European allies, while simultaneously deterring large-scale nuclear strikes against the U.S. homeland.

In other words, the United States built a larger nuclear arsenal than it needed to protect the U.S. homeland, because it chose to protect allies, too. This was the price to keep allies non-nuclear, which had the benefit of centralizing nuclear decision-making in the alliance in Washington. U.S. Cold War strategists sought to demonstrate a sufficient capability to credibly prevent nuclear attacks against European capitals, not just promise to retaliate after Warsaw Pact attacked them. This enabled U.S. policy makers to sidestep the question: Are you ready to trade New York for Paris? The U.S. postured itself to convince both Russia, but more importantly the ally, that it would never have to make that choice. In sum, the approach convinced other allies they did not need independent nuclear weapons—a key U.S. nonproliferation goal—and deterred the Soviet Union from military aggression against NATO. Simplicity subscribers know this is a drum we continue to bang.

Alongside the U.S. approach, the United Kingdom and France built limited arsenals designed to provide a survivable, strategic deterrent against Russia, but not one designed to deter limited conventional or nuclear attacks against others. The U.K.’s “Moscow Criterion,” for example, is a doctrinal benchmark whereby U.K. nuclear forces needed the ability to retaliate against Russia’s capital in response to nuclear strikes against U.K. territory, with survivable ballistic missile submarines forming the entirety of the U.K. force. The United Kingdom explicitly commits its force to NATO, albeit in partnership with the United States and as an avowedly junior partner (with all due respect to our special friends in London!).

France maintains a famously independent nuclear arsenal, reiterated by Macron last week, comprised of survivable submarines carrying strategic nuclear forces and fighter aircraft capable of carrying a standoff air launched nuclear weapon which is designed, in French strategy, to be flexible and probably the primary platform for the “final warning” indicating French readiness to escalate a conflict with its submarine forces. President Macron is the most outspoken European leader regarding the need to revisit nuclear deterrence on the continent, stating recently that France’s “vital interests” under its nuclear doctrine have a “European dimension.” The current French assessment of strategic “strict sufficiency”—historically, being capable of inflicting as much damage on Russia as France “is worth”—yields a stockpile of less than three hundred warheads. This assessment will likely need to change if France seeks to credibly extend nuclear deterrence to other allies.

Over the course of the Cold War, additional conventional forces supplemented the U.S. nuclear weapons, including increasing contributions by allies. Today, NATO enjoys a substantial conventional advantage over Russia, sufficient to make the Kremlin think twice about attacking a member state. Even as nuclear arsenals reduced in overall size, the U.S. nuclear forces, in combination with UK and French deterrents, presents a strong allied nuclear deterrent against a Russia that over-compensates conventional inferiority with nuclear weapons. The United States greatly diminished the proportion of conventional military strength it provided over time, while maintaining a greater responsibility for nuclear deterrence. Compared to the Cold War costs of massive forward-deployed conventional forces, the U.S. and allied deterrence game plan is far more affordable to the United States. The savings the new administration may seek by reducing U.S. nuclear commitments are not substantial.

Trust is Everything

In the past few weeks, European leaders have been questioning the credibility of the U.S. nuclear guarantee in unprecedented ways, not seen even during the Cold War. This nuclear crisis of confidence is a byproduct of the new administration’s approaches toward Russia, Ukraine, and European security. More recently, the possibility emerged that Washington will only provide Article V defense commitments to allies that meet a certain defense spending threshold. Publicly musings about absorbing Canada and Greenland, territory of fellow NATO members, feed into the growing unease.

The fundamental concern is not that the United States will withdraw its nuclear forces from Europe or stop nuclear and other military planning for Russia, but that it—and President Trump specifically—would not be willing to use force to defend Allies or, frankly, expend any effort to defend them. For this reason,

Non-nuclear European powers are also expressing interest in alternatives to newly ambiguous U.S. commitments. Germany’s Friedrich Merz, soon to be Chancellor, welcomes a discussion on “sharing” nuclear weapons with France and Britain, while viewing such a scheme as no substitute for U.S. nuclear guarantees. Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk made similar statements regarding access to nuclear weapons, though was ambiguous as to whether Poland required its own arsenal or could rely on France, while also threatening current contracts with Starlink presumably to put pressure on the White House. President Duda called for the deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons to Polish territory, which Vice President Vance promptly doused in Cold water. President Macron intends to follow-up remarks regarding extending France’s nuclear deterrent to protect Europe with a more detailed conversation, though it does not sound like nuclear deterrence was a topic of discussion at the recent E5 Defence Minister meeting in Paris.

The Euro Deterrence Problem, In a Nutshell

Reviewing nuclear deterrence in Europe is a much-needed though chilling conversation for Transatlantic leaders to initiate.

If London and Paris no longer believe the United States will use its strategic deterrent to guarantee Europe’s defense, they are left with a larger nuclear deterrence mission than ever before. While Russia’s conventional strength is far less than it was during the Cold War (weaker now after willfully throwing itself into the gristmill of Ukrainian defenses for three years) it will still pose a formidable threat to Europe. London and France cannot discount they may need to threaten first nuclear use to deter a future war, an exceedingly difficult option to make credible against Russia. Furthermore, U.K. and French strategic forces are ill-equipped to threaten retaliation against Russian limited nuclear use on allied territory, as they invite an overwhelming Russian attack against their territory against which they cannot limit through offensive or defensive capabilities. Therefore, there are strong incentives for the United Kingdom and France to “sit out” a brewing nuclear conflict with Russia to protect their own populations from strategic attacks. Russia knows this hesitation exists in a war and may then feel comfortable using nuclear weapons early in a conflict.

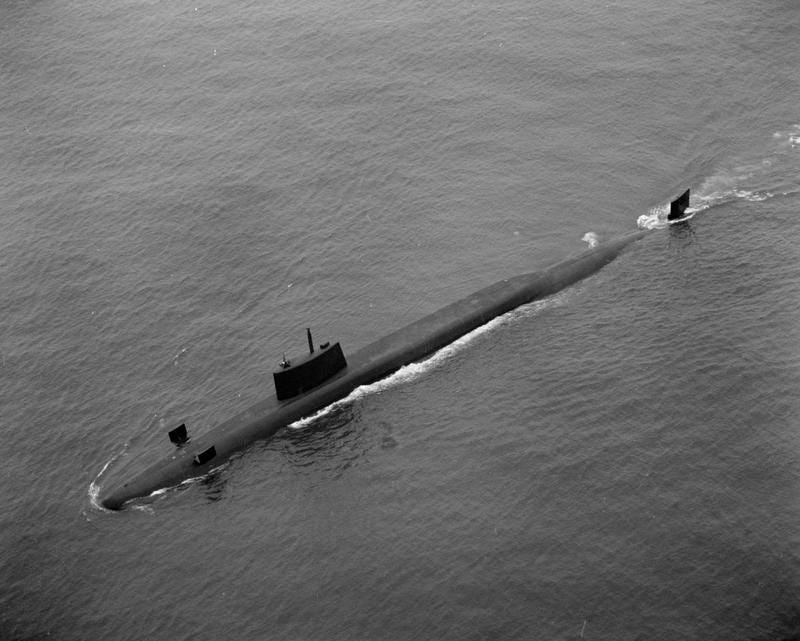

The deterrence challenge is derived from two primary gaps that London and Paris face. The first is in limited nuclear options. The United States stations B61 nuclear gravity bombs and dual-capable fighter aircraft in NATO countries, offering an in-region capability with limited yield to deter similar limited Russian nuclear attacks clearly divided from the U.S. strategic forces, whose use would signal an escalation from regional to strategic conflict. A legacy of the Cold War, forward deployed U.S. nuclear forces offers the chance (however small) that the scope and scale of escalation in a European war could be managed, avoiding an all-out nuclear exchange with far greater global consequences. The U.K. has just a single nuclear platform, the Vanguard class ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) which carries its strategic nuclear forces and, perhaps, a lower yield warhead as well. However, employment of the lower yield warhead would require use of a strategic missile (a Trident II D5 missile), costly given the small overall number of missiles the United Kingdom can deploy. Additionally, this limited use would likely reveal the location of the U.K.’s lone submarine at sea, risking the entire retaliatory capability it needs to deter attacks against U.K. territory. France’s primary nuclear delivery platform is also an SSBN, the Triomphant class. Neither French nor U.K. submarines offer a credible limited nuclear option, as each country only deploys a small number of their sea-based contingent at a time, creating strong motivation to keep them hidden as a survivable second-strike force to deter Russian attacks against Paris and London. Simply put, the SSBN-based limited nuclear option for a Euro Deterrent is in practice almost unusable.

France does have capability beyond its submarine-based strategic deterrent. France’s Rafale fighter aircraft can carry ASMP-A nuclear-armed cruise missiles, and could operate from other nations, an idea French experts raised in recent days. However, France possesses a relatively small number of these aircraft, which also have responsibility for conventional strike, carrier defense, and air dominance missions. Currently, only two squadrons are currently assigned to a nuclear deterrence mission (with some carrier-based aircraft available for nuclear missions as well). The cruise missile they can carry has a relatively high yield, at 300 kilotons (though some sources suggest the warhead may have variable yield), and France likely only possesses around one missile per nuclear-capable Rafale. A more credible limited nuclear option than an SSBN, France still considers the air leg an important part of its strategic deterrent, not ready-made for use in limited war contexts.

It is possible that France could utilize ASMP-As for forward deployment similar to NATO nuclear sharing of U.S. B61 bombs, but it would have to adjust its posture significantly. First, France would likely need more missiles and warheads as noted above. Second, it would have to develop concepts of operations and even basing schemes that run afoul of the French DNA of liberte nucleaire. If France chooses to adjust its posture to reassure allies, Macron could devise a forward-basing scheme and refit additional Rafale fighters to meet the “nuclear-capable” standard. France could also expand the number of allied operators of the Rafale (currently Greece and Croatia are the other NATO members who operate Rafale, and only Greece has past experience hosting nuclear weapons and aircraft), allowing other allies to participate in the nuclear deterrence mission similar to NATO’s current nuclear sharing approach. France would likely reject the latter idea, being historically opposed to bringing any shared decision-making or foreign role into its independent nuclear forces (a point Macron reiterated in his recent remarks). However, Paris must consider these steps as part of the Euro Deterrent conversation if Macron is serious about enhancing nuclear deterrence in Europe without American help, as no other easy options exist.

Posture shifts are more difficult for the United Kingdom. The U.K. Strategic Defense Review is examining the “efficiency and effectiveness of the nuclear programme,” with “NATO first” in mind. The SDR began before the new administration took office and shifted U.S. policy dramatically, and presumably U.K. officials are reconsidering certain initial findings regarding the role the U.S. nuclear deterrent plays. The United Kingdom does not have an easy solution to diversifying its nuclear force. The U.K. nuclear deterrent is heavily integrated with that of the United States. The United Kingdom produces its own nuclear warheads, but works closely with the United States through the 1958 Mutual Defense Agreement to share nuclear technology, materials, and information for defense purposes. Most importantly, the United Kingdom uses its indigenous warhead with the U.S.-developed Trident missile and cooperates substantially with the United States on naval nuclear propulsion. If the United States pulls back its commitment to the defense of Europe, there is a possibility that it withdraws cooperation with the U.K. on programs without which the U.K. could not even complete its planned modernization to Dreadnaught-class SSBNs, let alone grow or diversify its posture. While unlikely, influential British voices are concerned that U.S.-U.K. nuclear cooperation may not be safe from the Administration’s policy reviews.

The second major gap confronting a Euro Deterrent force is that it has no way to manage escalation even if the U.K. developed, or France extended, flexible regional nuclear capabilities. French and U.K. nuclear strategy has never operated without the U.S. strategic backstop. Take away U.S. forces, and Russia simply has overmatch. Moscow can respond to any limited U.K. or French employment with such devastating nuclear carnage that Western Europe would cease to exist as a functioning society. Replacing the strategic forces of the United States is an impossible task for a Euro Deterrent.

One Path Ahead

The United Kingdom and France may attempt to adjust their nuclear forces and strategies to account for a reduced U.S. nuclear commitment. But it is a tall task beyond mere words. Doing so as part of a comprehensive plan to adjust Europe’s approach to nuclear deterrence in light of a reduced U.S. conventional footprint could be conceivable and even prudent. All three countries, and their allies, need to discuss the requirements for deterring Russia from waging military aggression against Europe, how those requirements are currently met by U.S. conventional and nuclear capabilities, and to what extent they can be addressed by modified U.K. and French capabilities (as well as the non-nuclear support other European allies can provide). The Alliance will need a common understanding of the overall future U.S. force presence in Europe, forward-deployed nuclear weapons, and the U.S. nuclear backstop, to inform any new U.K. and French extended deterrence guarantees to other allies. Ideally, any changes to the U.S. posture will fit into a timeline to pace any U.K. and French increases to their deterrent capabilities.

However, it is inconceivable that their combined arsenals will replace what the United States provides anytime soon. Increasing the credibility of a Euro Deterrent can only happen if the U.S. nuclear guarantee remains. The image of a pooled U.K.-France deterrent facing off against Russia’s 5,000-plus nuclear weapons will not reassure allies. In fact, in such a world, allies and partners like Poland and Ukraine will consider how quickly they can get the bomb, further fragmenting the Alliance and nonproliferation regime. As we discussed, multiple new nuclear armed states, and multiple new nuclear decision-making centers, creates a far less stable Europe.

Allies must determine whether statements by administration officials change anything regarding current U.S. extended deterrence policy. The latter issue is likely the most important to resolve, but perhaps the most difficult to address, as senior officials up to and including the President question and attempt to leverage the bedrock of the Transatlantic alliance—the U.S. promise to defend European allies. Regardless, there is no Euro Deterrent without the United States. U.K., French, German, Polish, and other European leaders must pressure the United States to retain its nuclear promise, in part by demonstrating their willingness to entertain a conversation about further accepting the burden of defending Europe in certain domains (this approach seems consistent with European efforts to keep Washington on sides in ongoing Ukraine discussions). In exchange, European leaders must request that the administration make a fulsome, public commitment to Europe, backstopped by the full capabilities the U.S. military could bring to bear in a conflict, to rebuild trust with the governments and European populations that now worry about a nuclear abandonment.

Concluding Thoughts.

There may be a future where Europe can deter Russian strategic attacks without the aid of the United States. But that is a world that has never existed since the atomic age began, and it is hard to imagine in the foreseeable future, regardless of the verve European leaders now exude for the debate. Perhaps it is implicitly obvious in the tone of this article, but U.S. interests are likely to suffer whether the Euro Deterrent debate results in a “good” approach or not, as U.S. credibility, economic well-being, nonproliferation policy, and a plethora of other non-deterrence issues are at stake. The extended deterrence marriage was never one of convenience, but of shared necessity and interest, a bargain that was good for Washington and its European allies. Hopefully allies coordinate an approach to bring the United States back into the fold, rather than embarking on an unconvincing series of half measures to build a European nuclear deterrent.

A very interesting treatment of this issue which I’m sure is going to gather more attention in the months ahead. However, the claim that “nuclear deterrence has been at the core of NATO’s mutual security guarantee and collective defence since 1949” is historically misleading. At NATO’s founding, only the U.S. possessed nuclear weapons; the Soviet Union tested its first device later that year, the UK not until 1952, and France only in 1960—despite strong U.S. opposition.

NATO’s formation was rooted more in conventional military considerations than nuclear ones. As Lord Ismay famously summarized, the Alliance’s goal was “to keep the Americans in, the Russians out, and the Germans down.” The primary threat was perceived to be a Soviet armored offensive through Central Europe, and NATO’s European conventional forces were always seen as weaker in both quality and quantity compared to the Warsaw Pact.

U.S. nuclear forces were positioned in Europe, but American threat assessments often exaggerated Soviet capabilities to pressure allies into higher defense spending—largely to purchase American weapons. Notably, France has always maintained an independent deterrent and has never relied on the so-called American “nuclear umbrella.” The UK, after several failed delivery systems (e.g., Blue Steel, Blue Streak), became dependent on U.S. technology, ultimately adopting Polaris and now Trident SLBMs. Today, the UK’s nuclear posture is so tightly integrated with the U.S. that it no longer constitutes an independent European deterrent in any meaningful sense—unlike France’s force de frappe.

For a deeper dive into this subject, I invite readers to check out Ariadne’s latest dispatch on Substack: https://ariadnesdispatches.substack.com/p/why-nato-needs-ukraine?r=4ijqvu&utm_medium=ios.