SIGINT and SRTs in the Cold War

A Response to Aaron Bateman

History and political science are driven by the discovery and evaluation of evidence from a variety of sources. Scholars can then debate the conclusions drawn based on this evidence, with that dialogue pushing out the frontiers of knowledge. In that spirit I appreciate Aaron Bateman’s recent(ish) critique of some of my work with Brendan Green on the ability of the United States to find Soviet mobile ICBMs (also known as strategic relocatable targets or SRTs) during the late Cold War. However, Bateman’s critique is not nearly as dispositive as he suggests, particularly given evidence that has become available in the decade since my work with Brendan was published. This post will review our claims, Bateman’s critique, and provide a response to that critique with new evidence. While the available evidence is not dispositive, it now seems clear that before the end of the Cold War the United States had tested the use of SIGINT satellites to track Soviet mobile missiles and at a minimum some foreign sources believed that it had a degree of success in this effort.

Stalking the Secure Second Strike, SRT Style

In 2015, Brendan Green and I published an article on U.S. intelligence collection for counterforce targeting, the punchline being that U.S. intelligence was often much better than those without access to classified information believe(d). In a section on finding SRTs we noted that much remained classified but a few observations could be made:

The Soviet Union began developing two mobile ICBMs near the end of the Cold War: the rail mobile SS-24 and the road mobile SS-25. The SS-25 was deployed in 1985 and perhaps not coincidentally National Security Decision Directive (NSDD) 178 was issued in July of that year. The focus of NSDD 178 was strategic modernization and one of the key tasks was ‘[o]n an urgent basis, develop a program to provide a capability to attack relocatable targets with US strategic forces.’ A declassified official NSA [National Security Agency] history further clarifies that the standard required was robust, requiring ‘… the ability to destroy at least 50–75 percent of the [Soviet] force.

NSDD 178 led to the creation of the Mobile Missile Task Force, an intelligence community and Department of Defense organization focused on generating the intelligence needed to target Soviet mobile ICBMs. The task force was well funded and very high priority, but at present much of what the task force did and any possible successes remain classified. However, some suggestive information is available about two different but complementary efforts to track Soviet mobile missiles.

The first effort used SIGINT to track mobile missiles. Contrary to assertions that mobile missiles would be unlikely to emit detectable signals, there is good reason to believe that mobile ICBMs communicated with their higher headquarters with some frequency. In addition, mobile ICBMs are not typically operated as single transporter-erector launchers (TELs). There is a mobile command center, a support vehicle carrying supplies and a field kitchen for the crew, a massive fuel tanker, and at least one security vehicle. Communications between these vehicles can also potentially be intercepted and used to locate the vehicles.

There are two possible ways in which SIGINT could have been effective in tracking Soviet mobile ICBMs. The first is geolocation of transmissions originating from the mobile missile complex. This technique uses multiple observations of the same signal to determine the area where the signal originated. It can be employed relatively rapidly if different receivers that are geographically and geometrically dispersed but linked by communications systems observe the signal simultaneously. The US Navy is reported to operate a set of satellites in low earth orbit to locate ships using this technique.

However, this technique has limits when intercepting signals using only satellite systems. Reports on the Navy system noted above indicate that the emitter location can only be narrowed down to an area several kilometers in size. It is therefore unlikely that this technique alone was useful in tracking Soviet mobile ICBMs…

Exactly what NSA accomplished against mobile missiles is unknown, but there are several suggestive pieces of evidence in the public record. The NSA history, for example, spends two pages describing NSA’s contribution to the anti-mobile effort that have been completely redacted during declassification. A Russian military officer, referencing Western media sources, implies SIGINT collection from geosynchronous and high orbit satellites was quite successful. This source notes:

The results of satellite reconnaissance over the past decades have been carefully concealed and only a few of them have been published in periodicals. One such result is the surveillance of Soviet rail-mobile missile complexes (the SS-24 ICBM). According to data in the Western press, the location of these complexes was revealed in the 1980s through intercepts of the exchange of encoded radio signals between the combat complexes and the missile forces’ command centers.

Intelligence historian Matthew Aid also argues NSA was successful in intercepting SS-24 communication and adds that it intercepted communications of the SS-20, a mobile theater missile, as well. The same techniques would likely have been effective against the SS-25.

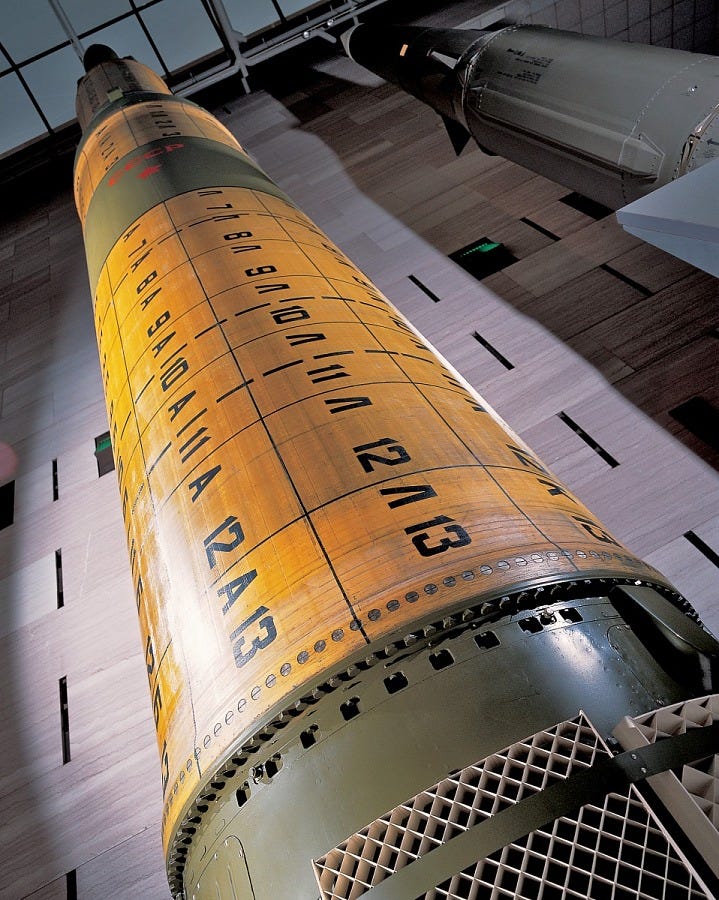

SS-20 missile at the Smithsonian Air and Space museum

Bateman’s Critique

In 2024, Aaron Bateman published an article critiquing the argument above using declassified sources. In this article he states (and I have included links to his sources):

Some security studies scholars argue that NRP [National Reconnaissance Program] SIGINT satellites were likely able to locate Soviet mobile missiles in a timely manner, but recently declassified documents call into question their hypothesis. The limited archival record available suggests that NRP assets were unable to adequately track and target Soviet mobile missiles through the end of the Cold War. Senior U.S. officials definitively stated that ‘we have no ability to effectively target Soviet mobile ICBMs, nor are we likely to have such a capability in the near future.’ In response to this challenge, in 1986 Director of Central Intelligence William Casey had established a mobile missile task force that became a joint effort with the Department of Defense in 1987. This group developed a set of recommendations for the sensors, command and control, and force structure ‘required to attack relocatable targets.’

In early 1988, the head of the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board further highlighted the relocatable target problem, underscoring the limitations of NRP assets. It is not clear what, if any, new systems were initiated to improve U.S. tracking and targeting of Soviet mobile missiles by the end of the Cold War. While the integration of NRP assets with tactical military units certainly improved their ability to carry out functions like long-range precision strikes, these satellites were insufficient for finding mobile missiles that were specifically intended to evade U.S. technical monitoring capabilities.

This is a fairly bold refutation of the argument that Brendan and I made, with the last sentence in particular being definitive. It is therefore worth interrogating the evidence Bateman provides as well as some of the logic.

His first source, from the Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS) series, is an attachment to “Memorandum From the President’s Assistant for National Security Affairs (Carlucci) to President Reagan” dated November 19, 1987. This memorandum was intended to prepare Reagan for an upcoming summit with Gorbachev and focused on nuclear issues from an arms control perspective. The attachment itself is undated but based on the date of the memorandum it is attached it must have been completed no later than November 1987.

Bateman rightly comments in a footnote on this source:

It is important to note that this comment about the limitations of reconnaissance satellites in targeting mobile missiles took place in the context of discussions about arms control verification. But it is reasonable to maintain that the limits of reconnaissance satellites in monitoring mobile missiles would be the same in both an arms control verification role and in a wartime surveillance and targeting role.

Yet wartime targeting and arms control verification ARE different. In particular for SIGINT, targeted forces must be operating in a way that produces electronic/radio frequency emissions. From a targeting perspective, mobile missiles must be deployed out of garrison to be survivable- and it is precisely when they are out of garrison they are most likely to emit. In contrast, from an arms control perspective covertly produced mobile missiles that remained undeployed and non-operational (e.g. stored in a warehouse or bunker) would not emit and SIGINT would have nothing to collect.

Even if one could determine through other means (imagery perhaps) where non-operational mobile missiles were being stored (and missiles and TELs could be stored separately), one would have a hard time verifying numerical limits were being maintained unless one could see inside the building. Indeed, even then it might be difficult if the mobiles were covertly produced, stored in a disaggregated, non-operational fashion, and perhaps shuffled around between sites. This force would not be immediately useful for deterrence and nuclear operations but could provide a ready breakout capability if arms control collapsed.

Bateman’s source notes the challenges that this fact causes for any form of verification of numerical limits:

Limits on mobile ballistic missiles present some of the most difficult verification problems in the strategic arena. With comprehensive verification measures like those developed for INF [Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces] missiles we could have [11 lines not declassified] Verification of mobile ICBMs is discussed in detail in GRIP 34; there is as yet no interagency agreement on the details (or even the existence) of an effective verification scheme for mobile ICBMs… The stability concerns arise from the reload capability and cheating potential associated with mobile ICBMs, especially (but not exclusively) large, highly fractionated ones. [9 lines not declassified]

Note that the detailed paper on verification referenced (GRIP 34) has not apparently been found by the FRUS historians. Further much of the discussion related to lessons from INF, reload potential, and especially cheating potential (potentially of the kind I described) was not declassified so there is still a lot we don’t know.

His third source is also from FRUS, a Memorandum From Secretary of Defense Carlucci to the President’s Assistant for National Security Affairs (Powell), dated March 2, 1988, regarding a letter from the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board (PFIAB). This source notes:

The PFIAB’s concern about the implications of permitting mobile ICBMs is also well founded. The latest NIE [National Intelligence Estimate] supports the Board’s view that we cannot confidently monitor a numerical limit on mobiles on the basis of NTM [national technical means] alone. The PFIAB also states that on-site inspection “cannot overcome these uncertainties,” and notes that “there are limits to the compliance gains that can be hoped for from any inspection regime,” as well as security and counterintelligence interests that require protection. The Intelligence Community has concluded that we need unlimited suspect site inspection to have a chance of detecting covert mobiles. But even such a regime will not be able to eliminate the risk of undetected Soviet cheating.

This is important additional context, as it suggests the concern about the limits of NTM (a euphemism for overhead collection) for verification was principally of the kind I articulated above, which was not about operational and deployed forces but rather non-deployed/covert missiles that cheated on limits for future potential breakout. If the concern was about operational forces- i.e. those ready to deploy out of garrison on patrol while armed with nuclear weapons- “unlimited suspect site inspection” would be likely to detect them. These forces would have a signature in garrison that includes security forces, fuel tankers, nuclear weapons storage and security, command and control systems, etc. These forces would also potentially emit radio signals when out of garrison (as discussed more below). All of this is much more plausibly detected by NTM and unlimited inspection than, for example, TELs stored separately from missiles and warheads.

SS-25 on parade. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

New Evidence on SIGINT and SRTs

Beyond the evidence Bateman provides noted above, other new evidence has become available since my original publication with Brendan. The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) has declassified a great deal of information about SIGINT satellites that supported U.S. Navy ocean surveillance (some of which Bateman cites). This includes the low earth orbit (LEO) POPPY satellite constellation, which operated as part of NRO’s Program C from 1962-1977, and the successors to POPPY, known as PARCAE and Improved PARCAE, which operated from 1976-2008. These satellites geolocated Soviet systems, particularly Soviet shipborne emitters like radar. While the declassified information does not include the precise accuracy with which these constellations could locate Soviet emitters, it indicates these systems were capable initially and grew more capable in the evolution from POPPY to PARCAE to Improved PARCAE. In principle, the same techniques and evolution could support geolocating mobile missiles.

More importantly, in 2023 NSA declassified additional portions of the history that Brendan and I cited in our 2015 publication. This new information includes something on NSA’s efforts following NSDD-178 and the establishment of the Mobile Missile Task Force:

From NSA’s perspective, this meant a period of very intensive research. It would be essential to zero in on all possible communications associated with SS-20 and SS-25 deployments, and this meant being able to commandeer overheard systems almost at will. Using NSDD-178 as justification, NSA designed a test under the name Project [redacted]. The starting point would be the three SIGINT satellites- [redacted] and the test would be divided into two periods in 1986. Photographic satellites would be brought into the test using [redacted] techniques.

This is important for three reasons- first it provides declassified confirmation that U.S. SIGINT satellites were explored as part of the effort to target Soviet mobile missiles. Second, it provides some important context to the timing of Bateman’s evidence. NSA apparently began experimenting with SIGINT satellites only in 1986 so we should not be surprised if in 1987 this test had not yet yielded the ability “to effectively target Soviet mobile ICBMs” as Bateman’s source (the Arms Control Support Group paper from sometime prior to November 1987) notes. Nor would it be surprising if this group was unaware of the NSA test and any results of the test when it wrote that the United States was not “likely to have such a capability in the near future.”

Third, it suggests NSA believed that deployed SS-20 and SS-25 at least possibly had communications that could be exploited. This last point aligns with Soviet sources. In addition to the Russian military journal Brendan and I cited in 2015, a file in the Kataev archive at the Hoover Institution provides much more granular detail on Soviet concerns about mobile missile geolocation from SIGINT satellites. As Brendan and I cited in a 2017 article, in an undated memorandum entitled “Monitoring and Intelligence,” Soviet analyst N.A. Brusnitsyn noted Soviet perceptions of US signals intelligence capabilities:

Eight satellites in stationary orbit of the ‘Chalet’ and ‘Rhyolite’ type exercise detection and interception of radio relay trunks of the national [communications]network… 2 new generation satellites ‘Aquacade’/‘Magnum’ in stationary orbit are intercepting radio and radio-technical emissions and eavesdropping on radio channels in an extended frequency range... [with] very high sensitivity and accuracy for locating radiating objects.

Brusnitsyn described the implications of these capabilities:

…even in adverse weather conditions and at night time monitoring from space through technical means proves [possible] not only for large military units but even for specific pieces of military equipment… Multiposition receivers capable of receiving a diverse array of signals with very large antennas in geostationary orbit combined with adaptive signal processing techniques provide complete monitoring of moving targets: on the ground, mobile missile systems; in space, missiles and warheads.

Thus it is clear both NSA and the Soviets thought it was plausible to geolocate and target mobile missiles through the use of existing overhead SIGINT satellites. What is unclear is whether NSA conducted the 1986 test or, if it did, whether it was able to convert this test of plausibility into an effective operational system. Bateman’s evidence strongly suggests it had not by 1987 but does not say much about the period after that other than speculatively from an arms control perspective. One of Bateman’s other sources notes the overall mobile missile tracking effort was still being funded with significant resources in 1989-1990, though this says nothing about the success of the NSA effort other than that resources were available. At least some foreign sources, such as the Russian military journal Brendan and I cite, believe that NSA was successful but this is far from dispositive.

Conclusion

Science advances by just this sort of dialogue and I again thank Aaron Bateman for engaging with our work. It remains unclear whether U.S. SIGINT satellites could enable effective targeting of Soviet SRTs during the Cold War- though it is more clear now that NSA tested the idea and had resources to pursue it. It is very possible these satellites could not find SRTs even if some Soviets believed they could- but the totality of evidence equally does not support Bateman’s statement that “these satellites were insufficient for finding mobile missiles that were specifically intended to evade U.S. technical monitoring capabilities.” This could be true- but more and better evidence would be needed for the period after 1987 to support such an unequivocal assertion.

I would say that "the ability to destroy at least 50–75 percent" was not all that "robust." The Soviet Union, in fact, assumed a worse outcome - the "80 targets" in a retaliatory strike would mean that, say, only one out of 8 SS-24 trains and about 20% of SS-25 missiles would survive (that is, 30 SS-24 warheads plus 50 SS-25).